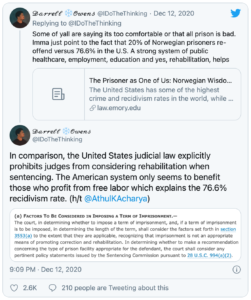

Does “United States judicial law explicitly prohibit[] judges from considering rehabilitation when sentencing“? Yes, says Darrell Owens, someone who has the right sympathies about the cruelty of American prisons, but not much of a grasp on the law. Any federal criminal lawyer knows that rehabilitation must be taken into account when a judge sentences a defendant.

Owens wrote these comments in the context of comparing American prisons to prisons in Nordic countries. And his point on that score is well-grounded. Many American prisons are cruel dungeons, generally unclean, unsafe, and not suitable for animals, much less human beings.

The United States suffers from high recidivism rates – the rate at which offenders commit new crimes and return to prison – in part, no doubt, because the federal Bureau of Prisons and state counterparts are underfunded and prioritize punishment and warehousing over rehabilitation and treatment.

But Owens is not correct when he says that “judicial law” prohibits judges from considering rehabilitation when sentencing.

In fact, earlier in December, the Fourth Circuit decided U.S. v. McCoy (20-6821) (see pdf). The Government had appealed federal District Judge Catherine Blake’s re-sentencings in three cases involving Hobbs Act robberies committed in the 1990s and early 2000s in which the defendants were also convicted of 18 U.S.C. Sec. 924(c) violations. 924(c) criminalizes the possession of a firearm in furtherance of a “crime of violence” or a serious drug felony. At the time, a conviction for violation of 924(c) meant a minimum of 5 years in prison consecutive to all other charges, followed by 25 years consecutive to all others for each additional offense.

For example, prior to the law being amended in 2018, a person convicted of three counts of 924(c) would face a minimum of 55 years in prison consecutive to other punishment. The law was used as a “plea extraction” tool by prosecutors, forcing people to plead guilty – instead of go to trial – to avoid astronomical sentences.

In the McCoy cases before the Judge Blake and the Fourth Circuit this fall, the defendants, mostly young, received 30 and 40 year sentences based on 924(c) stacking. Their criminal lawyers argued for reductions in each of the defendant’s sentences upon rehearing.

In rejecting the Government’s appeal and attempt to maintain these sentences, the Fourth Circuit specifically noted that rehabilitation is part of any sentencing decision made by a federal judge:

The district courts in these cases appropriately exercised the discretion conferred by Congress and cabined by the statutory requirements of § 3582(c)(1)(A). We see no error in their reliance on the length of the defendants’ sentences, and the dramatic degree to which they exceed what Congress now deems appropriate, in finding “extraordinary and compelling reasons” for potential sentence reductions. The courts took seriously the requirement that they conduct individualized inquiries, basing relief not only on the First Step Act’s change to sentencing law under § 924(c) but also on such factors as the defendants’ relative youth at the time of their offenses, their post-sentencing conduct and rehabilitation, and the very substantial terms of imprisonment they already served. Those individualized determinations were neither inconsistent with any “applicable” Sentencing Commission guidance nor tantamount to wholesale retroactive application of the First Step Act’s amendments to § 924(c). Accordingly, we affirm the judgments of the district courts. (emphasis added

Furthemore, 18 U.S.C. Sec. 3553(a) specifically refers to “correction” as one of the factors that a judge must consider:

The court, in determining the particular sentence to be imposed, shall consider…the need for the sentence imposed… to provide the defendant with needed educational or vocational training, medical care, or other correctional treatment in the most effective manner.

North Carolina – where I practice as a federal criminal lawyer – also instructs judges to consider rehabilitation.

While Darrell Owens is correct that American sentences are far too long and the prison system lacks either the desire or ability to adequately rehabilitate offenders, he is incorrect when he says that a federal criminal lawyer cannot argue to judges that they consider rehabilitation in fashioning an appropriate sentence.