Cell Phone Towers & Investigations

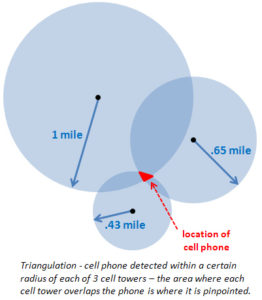

Can the Government get your historical cell tower data without a warrant? Cell phone data is used by law enforcement in order to try to pinpoint the location of a person during the commission of a crime. Even in idle mode, cell phones constantly ping towers, often pinging different nearby towers although the cell phone may be stationary.

Then the person carrying the cell phone moves, the cell phone will ping successive cell towers roughly showing the path that the person took. In addition, the radius around a cell phone tower is generally divided up into three quadrants or pizza pie slices. The operator of the cell phone can let police know which “slice” of the pizza pie received the contact with the cell phone.

The question is how the Fourth Amendment protection against warrantless searches applies.

Are Search Warrants Needed?

This data can be analyzed to determine routes, locations, and meeting points (when more than one suspect’s cell phone is in a particular location). In addition, by linking the cell phone data to billing records, police can sometimes determine when and, importantly, where a cell phone call was made.

The Government has long relied on two 1970s era cases for the proposition that its request for cell phone tower data does not first require a search warrant supported by probable cause.

However, as we all know, cell phones hardly existed in the 1970s. The first modern cell phones came on the market in the mid 1980s, and those phones were expensive and unreliable.

In Riley v. California, the Supreme Court, in a unanimous opinion, rules that cell phones themselves could not be searched, even incident to arrest, without a valid search warrant.

Criminal Case Before Supreme Court

In the fall, the Supreme Court is set to decide U.S. v. Carpenter, a case out of the Sixth Circuit, involving the retrospective tracking of a Carpenter’s movements. The case has been joined with U.S. v. Graham, a Fourth Circuit case, in which the government gathered nearly 30,000 data points generated by Aaron Graham over a 7 month period. Graham was later convicted of armed robbery in part based on the cell phone location data which put him near robbery locations at the time of the crimes.

In obtaining the cell phone data, the Government has relied upon the “third party doctrine,” a theory propounded in Smith v. Maryland, 442 U.S. 735 (1979) – and before the advent of cell phones – to claim that because Graham voluntarily turned over his location data to a third party – the cell phone company – presumably in order to use the cellphone, the Government ought to be able to obtain that data without a warrant.

The Electronic Freedom Foundation has called the theory a “wonky principle” that the Fourth Circuit stretched to allow the Government access to the most intimate details of our life without a warrant including our location at any point of the day over a seven-month-long period.

As the EFF noted, that “wonky” principle will be even more problematic owing to the Internet of Things, the devices embedded in washing machines, thermostats, cars, televisions, AppleTVs, Amazon Alexa devices, thermometers and so forth that may be available to the Government without a warrant if the Supreme Court upholds an expansive view of the “third party doctrine.”